How to Build Winning Campaigns: Relationships, Not Transactions

Campaigns are an exercise in relationship-building, but too many have forgotten

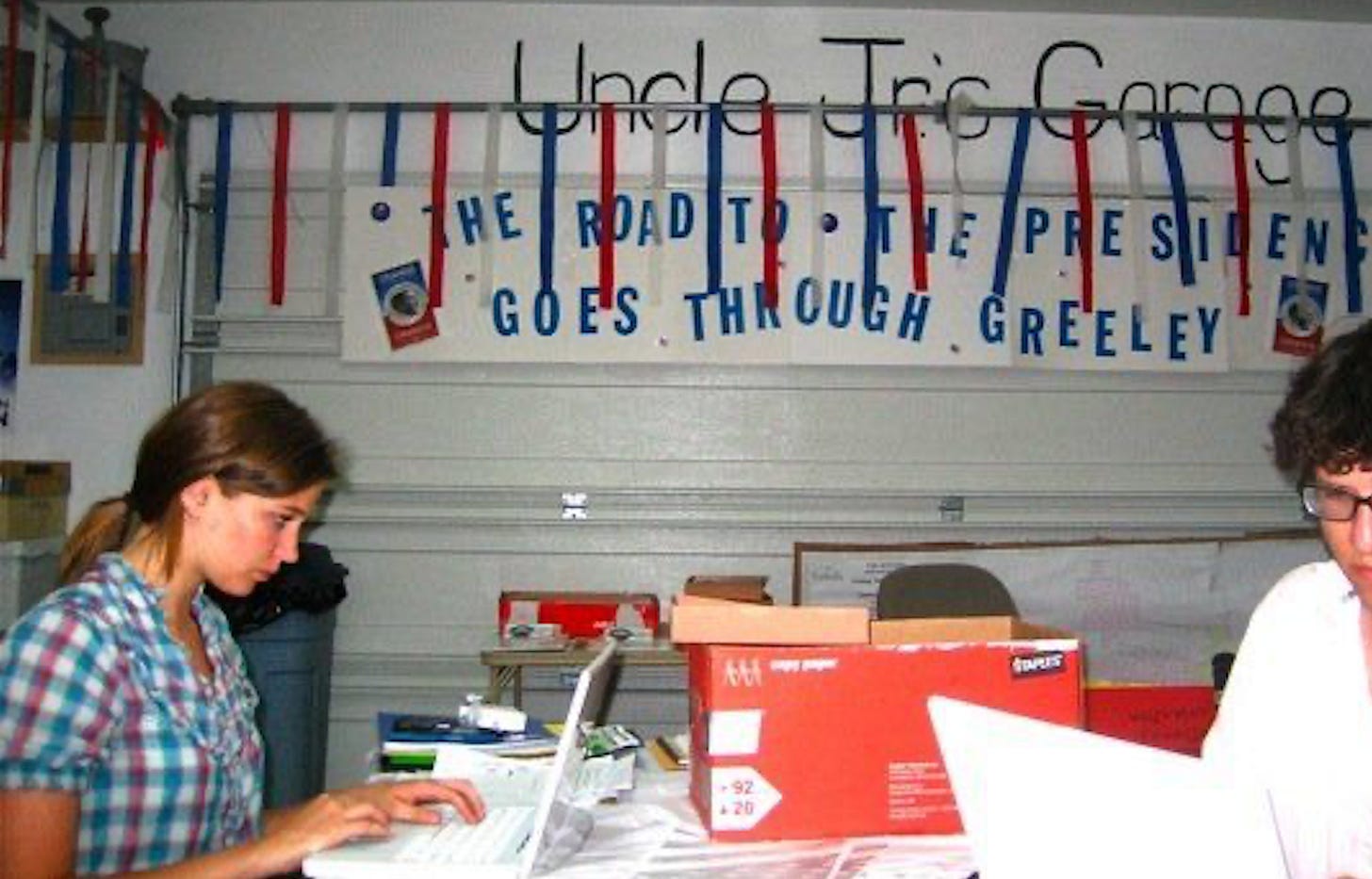

Working as an organizer in Greeley, Colorado during Barack Obama’s 2008 Campaign

My introduction to campaigns was working as an organizer on Barack Obama’s first Presidential in 2008. I was 21 years old, and I had volunteered a little in school, but had never worked as campaign staff before. I had just finished my junior year of college, and despite being a theater major who was confident playing a part on stage, I was very shy when it came to being myself in real life situations, especially those that involved talking to strangers. In June of that year, I moved to Colorado to become an organizer for the campaign. That summer, I spent hundreds of hours outside supermarkets, in parking lots and laundromats, and on street corners registering voters. Every evening, I returned to Uncle Jr.’s Garage (our makeshift office in-kinded by a beloved local volunteer), to make a hundred phone calls, recruiting Obama supporters to host house meetings that I would attend and facilitate on the weekends. That summer transformed my perspective, set a new trajectory for my life, and taught me powerful truths: I had real agency (we all do), my story mattered (everyone’s does), and forging personal connections with strangers — even in micro-interactions — is the stuff that powers movements and winning campaigns.

Being an organizer taught me that everything a campaign does—from the candidate’s speeches to the volunteers’ canvassing conversations to the text messages and advertisements —is all about building community around shared values and developing agency in others. That is the road map for inspiring action en masse: fostering shared purpose, building scalable networks of relationships, and empowering leaders with the resources and support they need to mobilize collective action.

As a community organizer influenced by Marshall Ganz, Obama knew this intuitively and embedded this ethos in both of his campaigns. In every field office across the country, you were sure to see a hand-made sign with the campaign’s motto: “Respect, Empower, Include”(We added “Win!” to the end of those signs in 2012).

It makes me feel old to say this, but as I’ve observed campaigns in the years since 2012, I’ve noticed many democratic campaigns have let the light of this wisdom dim and fade from their view. You can hear it in the language candidates use: employing “I” instead of “we,” addressing “you” instead of “us,” focusing on charts and stats and track records instead of vision and values and the stories that touch people’s hearts. Conversations about how we might use AI on campaigns seem to constantly return to content creation, rather than the automation of time-intensive or menial tasks that would free up [human] staff to use their creative talents to communicate. Fundraising emails that treat their recipients like ATMS are sent out daily with the-sky-is-falling subject lines, full of capital letters and superfluous exclamation points.

Organizing programs have become more like the old “field programs” that pre-dated 2008, more focused on contacts than conversations, more interested in volunteer shifts scheduled than volunteer leaders developed, more reliant on paid canvasses and mass texts (pro tip: adding a photo of the candidate before the message does not make a text feel more personal). In short, campaigns have become more transactional, less rooted in authenticity, and less relational.

That might sound lofty to some, but there are very real consequences to a transactional approach: winning campaigns require capacity, and capacity is built through decentralization of leadership; a model that harnesses the power of individuals as multipliers. You can’t decentralize leadership if you don’t recruit and develop leaders. And you can’t recruit and develop leaders without investing in relationship-building. One organizer alone might be able to recruit 20 canvassers to knock doors on a Saturday (~1,000 door knocks assuming 50 doors per volunteer), but one organizer with a team of five volunteer leaders to help them can recruit, train, and deploy 100 volunteers to knock doors on a Saturday (~5,000 door knocks). As competitive elections are often won by razor thin margins, these numbers can add up and make a very important difference.

There’s a qualitative difference too. While TV ads have been shown to have minimal effects on undecided voters, some of the most powerful persuasion effects we’ve ever observed have come through deep canvassing experiments, a relatively new approach to canvassing in which volunteers spend as long as 18 minutes at a voter’s door, asking non-judgmental questions, practicing active listening, and exchanging personal stories. One of the most effective turnout tactics political scientists have tested is now referred to as “relational contact,” in which voters are asked to reach out to their friends and families to encourage them to vote (also referred to as “Vote Tripling”).

The data is clear: a relational, human-to-human approach means more capacity, more persuasive conversations, and more votes. Sure, humanizing campaigns feel good, but they also win because elections are battles for trust.

My impression is that the Harris campaign understands this, and so do the movement leaders and community activists that have rallied around her since she became the presumptive nominee in July. But knowing what it takes to win, and doing what it takes to win are two different things. The tough reality is that Harris has only 60 days to build the infrastructure and capacity the campaign needs to reach, persuade, and mobilize voters in battleground states. For frame of reference (and since hope is making a comeback): on Obama’s re-election campaign, we began that project 19 months before Election Day, and every Presidential campaign since has started general election work at least six months before Election Day. Suffice it to say there’s a lot of work to be done, and relationships aren’t built overnight.

If you want to know how you can help Harris and Walz win the White House, here’s my advice: donate to the campaign (and candidates all the way down the ballot), text your friends, call your family, chat up your neighbors, write letters and post cards, get trained for GOTV, and go volunteer at a local field office or staging location (like Uncle Jr.’s Garage). Invest in making a personal connection, however small, during every interaction you have on the campaign’s behalf. Volunteer to talk to strangers. Share your story. Tell anyone who will listen about your “why.” Don’t worry too much about getting the words just right. Start by asking questions about the experiences that shape their perspective, and then tell them about yours. You might just make a few friends and discover your own sense of agency in the process. And who knows, it might even change your life.

I went to a democratic campaign event last week, and unfortunately nobody talked to me or anyone around us. We of course struck a conversation, which funny enough was about what we could do to help the campaign. There was unfortunately no direction from an organizer or volunteer, or someone who have followed up since. They aren't getting rid of me, and I will keep trying to help! :)

Great post and observation.

I was the top recruiter in California on a campaign where I was allowed/encouraged to have real conversations with people, using the same skills I'd used in my careers in sales and hospitality.

Now after 11 campaigns I just spent the last cycle with a state Dem party where metrics weren't the most important thing - they were the ONLY thing.

God forbid you have a conversation with more than a quick ask, after 90 seconds I'd get messages asking what was wrong, why had I stopped making calls? The organizers that dialed 2 phones at once & spoke with half as many voters got great metrics though, it felt like working as a telemarketer for a corporation.